Anaïs, Empress Eugenie and Baron Haussmann

A little bit of history

In the mid-19th century, Baron Haussmann made Paris a capital worthy of the splendours of the Second Empire. He demolished old neighborhoods, pierced large gas-lit boulevards, and designed public parks. He entrusted engineer Adolphe Alphand and architect Gabriel Davioud with the task of creating new urban furniture such as newsstands, columns, fountains and public benches whose bottle-green color recalls nature in the greyness of the city.

The double-seated bench with its grey cast iron base, the Parisian coat of arms engraved in the side supports, its oak slats became an iconic element of the urban landscape. And this fashion will spread to provincial cities. It was at the same time that Empress Eugénie fell in love with Biarritz and contrived to turn the small fishing-port into a fashionable seaside resort. It is probably at that same time that the promenades and panoramic views of Biarritz were set with the famous green benches.

According to urban planner Jean-Paul Alain “being able to sit is the mark of a friendly city”. But it goes much further: the benches are public benches offered free of charge to the inhabitants of the city. Previously you couldn’t sit down when you walked or you had to stop in a café or rent a chair in a park, a comfort that not everyone could afford. Generally speaking workers at that time worked standing up. In his novel Au bonheur des dames, Zola depicts the particularly difficult working condition of saleswomen on their feet for long hours. In The death of the poor, Baudelaire evokes the bliss that the wretched will finally enjoy:

It is death that consoles, alas! and which makes people live

…

It is the famous inn listed in the Book

Where you can eat and sleep and sit.

Public benches have allowed city dwellers, even the poorest, to make the city their own.

Public benches have stories to tell

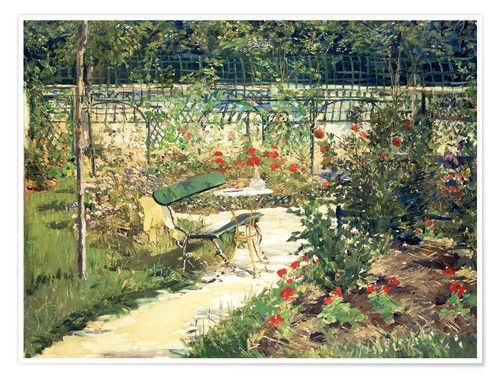

George Brassens’ song reminds us that public benches do not only allow the potbellied to catch their breath during a walk. They also promote forbidden love. It is also on a bench that the frail widow will feed her pigeons every day, that the little old man will tell his dog as old as he is stories of his youth, that a bashful lover will wait for a woman who will or will not show up, that a mother will tie the shoelaces of one of her children, that a homeless person will pause to grab a bite before resuming his wanderings. Sometimes we are alone on the bench but sometimes we have the opportunity to meet people whether relatives or strangers. The bench thus promotes social interaction. In this way it becomes an emblem of modern life, its fatigues, its sorrows, its joys, its solitude but also the hope of meeting a kindred spirit. Impressionist painting will mirror this. We can quote Dans la serre de Manet, Le Banc de Monet, Le banc du jardin de Versailles de Monet, Le Parc Monceau de Caillebotte.

Later cinema will exploit the poetic, romantic and even philosophical possibilities of the public bench (Forrest Gump by Robert Zemeckis or Les Bancs publics by Polyades which is a meditation on the solitude of modern man).

Anaïs Zhang’s paintings are part of this rich tradition. Many works in the bench series tell stories. It is up to the viewer to imagine them, to create the plot behind them.

“I am guided by what you see” says the Painter to her Model.

Let’s not forget the most important. In a city like Biarritz open to the sea, the bench allows you to contemplate a sublime scenic view. Anaïs Zhang often paints beings absorbed in the spectacle of the ocean, seen from behind. In a way the artist does not paint directly what she sees but a landscape seen through the prism of another look, that of the passer-by sitting on the bench. It is therefore a transitive, indirect look. The artist’s brushes give color and shape to the dreams and visions of the passer-by. Thus, the bench with its few wooden slats with flaking paint, placed facing the infinity of the ocean, turns out to be the crucible of poetic and romantic elaborations, the laboratory of emotions and artistic experiments.

Jeanne Verdun, April 2022